Coexistence among disciplines, humans and predators: Five Dimensions of Analysis for More Convivial Human-Predator Interactions

Transdiciplinary collaboration to better understand human-predator interactions

By Valentina Fiasco, Judith Krauss and the CONVIVA collective

Original article published in International Global Development Center

Understanding human-predator interactions has been a central goal of conservation for decades, yet many efforts have approached this challenge from disciplinary perspectives focused on single case studies. There is a need for more transdisciplinary and multi-sited research to enrich our understandings of the complexity of human-nonhuman interactions and to design ways to make them more convivial.

The multi-year CONVIVA “convivial conservation” research project addressed this gap, involving scholars from natural sciences, social sciences and humanities to promote coexistence, biodiversity and justice in conservation across four diverse case studies of apex predators: jaguars in Brazil, wolves in Finland, lions in Tanzania, and brown bears in California, United States.

In this blog, we set out two key contributions from our recent collective open-access article in Biological Conservation. First, we highlight how our project created iterative, dialogue-based reflections. As we brought together different academics and practitioners, we prioritised ongoing dialogue beyond silos to inform research questions, methods and units of analysis.

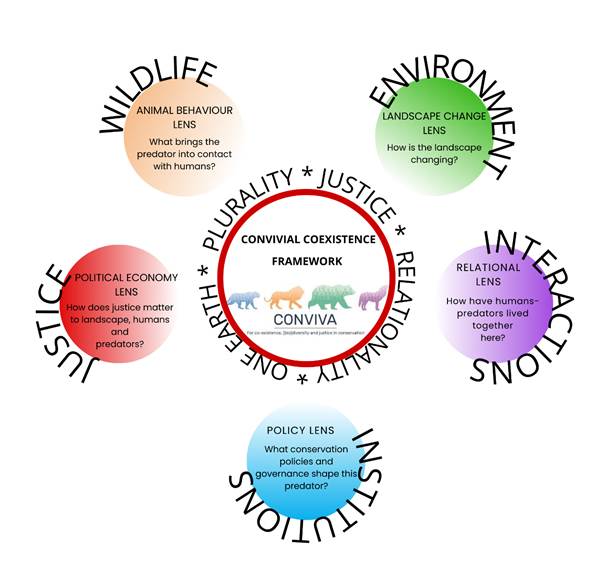

Second, we operationalise our collaboration into a novel framework of five interconnected dimensions of analysis of human-predator interactions: wildlife, environment, interactions, institutions and justice. We formulate a series of guiding questions and test our dimensions through empirical material from our cases.

Addressing existing gaps

Most research on human-carnivore interactions has focused on solving conflicts rather than promoting coexistence. They have also prioritised using technical solutions: predator deterrents, fences, compensation schemes, or payments for ecosystem services. While these tools have their place, they often sideline deeper, structural questions—like how history, politics, and power dynamics shape these interactions, and at whose expense. They also tend to overlook non-western knowledge systems and local perspectives.

Working toward coexistence requires understanding what it means in different contexts for different people (Fiasco & Massarella, 2022). This involves thinking and acting across different approaches, disciplines, sectors, and worldviews. Yet, as people and wildlife are often studied separately, inter- and transdisciplinary collaborations are frequently hindered.

We draw on convivial conservation, i.e. a vision, a politics and a set of governance principles’ that promotes ‘radical equity, structural transformation and environmental justice’ (Büscher and Fletcher, 2019: 283). The article aims to address gaps in existing literature by:

- Highlighting the importance of understanding power, political economy, and history when discussing coexistence.

- Prioritising bringing in diverse disciplines and backgrounds,

- Appreciating underrepresented knowledges.

- Shifting the focus beyond conflict towards coexistence.

Building dialogue into collaboration beyond disciplinary silos

Our work started with a series of workshops organised by the Brazilian (Laila Sandroni, Silvio Marchini) and US (Alex McInturff, Peter Alagona) teams of the CONVIVA project. The goal of these workshops, which brought together scholars and practitioners working in the project’s four cases, was to develop shared understandings and reflect on similarities and differences across contexts, cases and disciplinary perspectives.

The first workshop involved sharing a first version of the dimensions of analysis (Marchini et al., 2021), which all four country teams populated with insights ahead of the second workshop. In the Brazilian team’s second workshop, through an interactive game by Laila Sandroni, the teams were asked to guess what statements originated from what case-study and concerned what predator, highlighting parallels and differences. The emphasis on both geographical and disciplinary diversity reflected aspirations for researchers from the Global South to be heard and better recognised (e.g. Chapron and Lopez-Bao, 2020).

In follow-up workshops organised by the US team, we explored the factors that determined the success or failure of predator-focused interventions. We found four emerging themes: social trust, political economy, material consequences, and predator characteristics, and explored them through the empirical specificities of our predators and contexts.

Building on insights from our workshop series, we created a set of guiding questions, developed iteratively from our case studies, to explore five interconnected dimensions of analysis (the ‘what’) with related lenses (the ‘how’).

Five dimensions of analysis for more convivial human-predator interactions

Source: Valentina Fiasco

Wildlife dimension: animal behaviour lens

This dimension relates to the behaviours and actions of wildlife that shape interactions with humans. In this dimension, our main guiding question aimed at understanding what brings the predator in contact with humans. Therefore, it involves looking at biological and ecological data regarding diet, habitat, natality and mortality, movement, impact on crops or livestock and prey base. The idea is to understand the role of the predator in that ecosystem, compile information from research and local people to understand its behaviour, feeding habits, movements, and the ways and rate of its interactions with people.

We illustrate the relevance of this dimension with empirical material on jaguar conservation in Brazil, which is critical to the region’s ecology. However, conservation is shaped by local perceptions and actions that are still poorly understood and rarely considered, such as retaliation as jaguars are wrongly blamed for livestock or dogs being lost to pumas (Morato et al., 2013; Sandroni et al., 2022).

Environment dimension: landscape change lens

Here, the analysis is guided by geography, applied ecology and political ecology, and it explores anthropogenic and other environmental changes that affect predator conservation through a landscape lens, such as environmental degradation, land use change, urban and agricultural expansion and climate change. The aim is to understand how the landscape is changing over time, and how these changes (whether real or perceived) affect the predator, its interactions with people, and the potential for conflict.

We use the semi-arid to arid Ruaha-Rungwa ecosystem in Tanzania, the study site of CONVIVA Tanzania’s research team, to highlight that lion conservation has been shaped by economics, politics, environmental change, and international conservation efforts, with limited engagement or understanding of local land users (Kiwango & Mabele, 2022; Mabele et al., 2022).

Interacitons dimension: relational lens

In this dimension, guided by anthropology, ethnography, human behavioural psychology and human dimensions of wildlife, we direct attention to understanding how relations, attitudes and values towards wildlife affect human-predator interactions. Through this lens, understanding how predators and people have lived together also means examining the relationships between different worldviews and the power dynamics that shape them. This includes centring alternative ways of knowing, valuing and perceiving non-humans.

CONVIVA’s Finnish team explored attitudes and perceptions of wolves and wolf conservation in Lieksa, eastern Finland. Interviews and participant observation have demonstrated diverse viewpoints, yet also significant opposition towards wolf conservation despite economic damages from wolf depredation being relatively limited (Komi & Kroeger, 2022; Komi & Nygren, 2023).

Institutions dimension: policy lens

This analytical dimension highlights governmental policies and stakeholders’ decision-making that directly or indirectly influence conservation dynamics at different scales. This might include, for instance, looking at how specific policy and decision-making arrangements influence human-predator relations, the protection status of predator, prey or habitat, etc.

Using the Ruaha-Rungwa ecosystem, we examine the different types of protected areas present, the uses and benefits they entail for different groups, and the issues rising lion populations cause for those living alongside lions.

Justice dimension: political economy lens

In this dimension, we ask: how does justice matter to landscapes, humans and predators? Drawing on political economy and political ecology, we highlight how historical and contemporary economic and power relations linking to class, gender, race/ethnicity, generation, etc., intersect and affect conservation and human-predator interactions.

In the CONVIVA project, the California team explored potential reintroduction of brown bears, in certain habitats in California, United States. In discussions of any reintroduction, it will be essential to consider environmental justice, including multispecies, distributive, recognition and affective environmental justice (McInturff et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Our article sets out a blueprint for transdisciplinary collaboration and a framework to better understand human-predator interactions, rooted in convivial conservation (Massarella et al., 2021). Addressing shortcomings in existing literature, our approach focuses on power, political economy and history, overcomes disciplinary silos, celebrates plural knowledges beyond western science, and goes beyond conflict. We emphasised firstly the need to build into transdisciplinary projects collaborative, dialogue-based reflections, bringing together researchers and conservation practitioners from different disciplines. This iterative collaboration resulted in a framework of five interconnected dimensions of analysis and lenses with guiding questions to operationalise our insights.

In terms of key lessons, our dialogue-based process highlighted the advantages and challenges of working across disciplines. In our approach, we also sought to incorporate diverse knowledges and knowledge holders particularly through our Tanzanian and Brazilian examples. Thirdly, our analysis operationalises a consistent attention to structural imbalances in justice and power across diverse scales and parties. Finally, we shift focus from conflictual human-nonhuman connections to a continuum of interactions, while recognising that conflict can also be a part of coexistence.

Citation: Krauss, J. E., Fiasco, V., Marchini, S., McInturff, A., Sandroni, L. T., Alagona, P. S., Brockington, D., Büscher, B., Duffy, R., Ferraz, K. M. P. M. de B., Fletcher, R., Kiwango, W. A., Komi, S., Mabele, M. B., Massarella, K., & Nygren, A. (2025). Coexistence beyond disciplinary silos: Five dimensions of analysis for more convivial human-predator interactions. Biological Conservation, 308, 111145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111145