Confessions of a guerilla gardner: a photo essay

by Neelakshi Joshi

In the fall of 2021, after a long search, we finally found an apartment that we could afford in the city of Dresden. While the apartment was quite basic, what had attracted us a lot about this location was the lush common backyard. However, as spring came around we started noticing the relentless lawn mowing that was part of the housekeeping routine here. As soon as the grass, clovers, daisies and ribwort plantains managed to grow a few centimeters, the gardner appointed by the housing company would come and clear the whole area off. Again and again. Now, there is a lot of research showing the negative impacts of lawn mowing in cities. These include the loss of biodiversity, increase in runoff and the creation of sterile monocultures that are not resistant to heat and drought situations which are becoming increasingly common with climate change. So each time the mowing started, the researcher inside me had to grind her teeth in frustration. Reasoning with the gardner did not help as he said that he was only doing his job and following the regulations of the housing company. It was then that we decided to take things in our own hands.

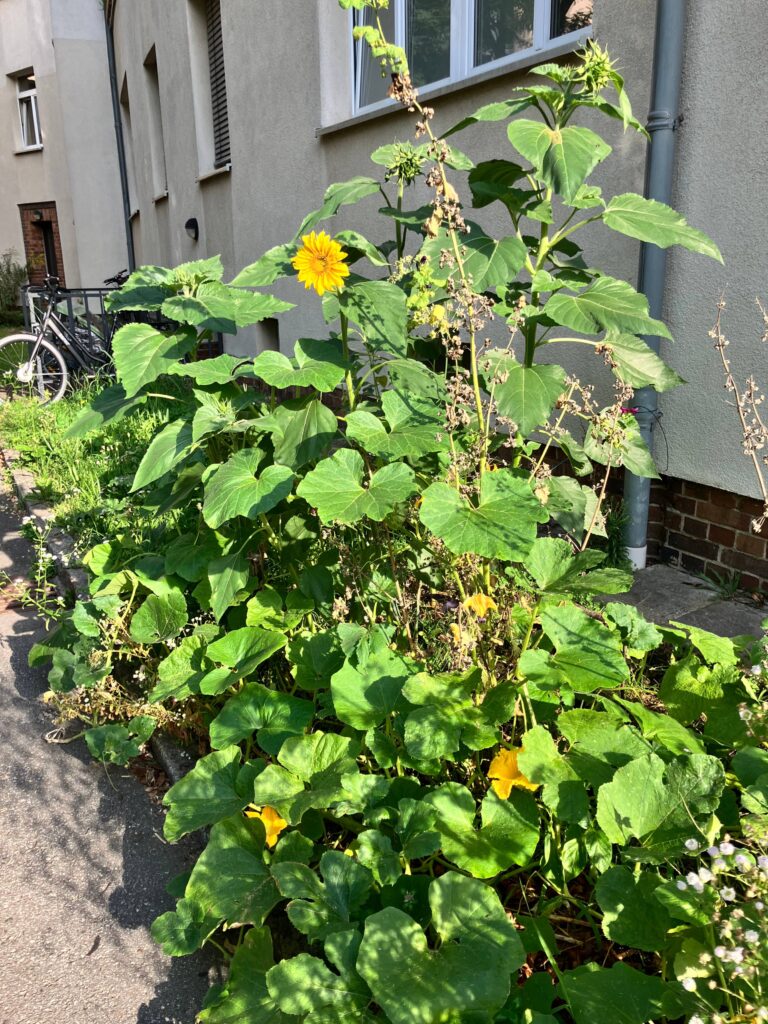

As any self-respecting gardner knows, the first step towards gardening is soil building. So, we started by collecting all our kitchen scraps and burying them in the small strips of land in front of our house. This was much needed because the soil had been ripped of nutrients by the monoculture short-cut lawn. As spring came, we planted some sunflowers, mallows, pumpkins in the land patch. When small shoots appeared, they were hardly distinguishable from the rest of the grass and we were afraid that they would be mowed away. At this point, we had another chat with the gardner. He was skeptical of our experiment but indulged us as long as we promised to take care of whatever we were trying to do.

By July the garden was in full swing. The pumpkin vine spread out, the sunflowers bloomed and the tomatoes began to ripen. Curious neighbours would stop and express their support for our garden. Kids would drop by and taste fresh tomatoes. Birds and bees became frequent visitors as did earthworms and ants. I spent a lot of time outside, sometimes just admiring the plants and collecting harvest at other times.

By the end of the growing season we had several harvests of pumpkins, tomatoes, potatoes and rucola (that planted and maintained itself). In fact, the first pumpkin of the season was presented to the gardner for being an ally in this experiment. I also cooked with pumpkin and tomato leaves and learnt a lot of new recipes using mallow flowers and leaves. We closed the season with several jars filled with dried herbs, packets full of seeds and a brain full of ideas for the next year.

Emboldened by the success of our first, we expanded operations moving to other “vacant” strips of land in the courtyard. The gardner now knew what we were doing and turned a blind eye. The neighbours resounded their support and extended help by taking care of the now growing garden during the times we were away during summer. Plants have gotten bigger, wilder and diverse in our courtyard. Some neighbours started similar plots in front of their blocks. Our grocery bill and food miles have reduced as has our frustration and helplessness on seeing land being mowed of life and dignity.

Guerilla gardening is an act of radical democracy and green grassroots activism where citizens take over empty, often uncared-for land and plant flowers, vegetables and fruits. This is often done without the permission of the owner, and sometimes in-spite of it. We were pushed by our irritation towards lawn mowing to take direct action. We were not hopeful of engaging with our housing company as they are usually indifferent to residents’ needs. So, we created an alternative landscape, starting with the patches of land closest to us. Sensing support from the neighbours as well as from the land, that surprised us by blossoming beyond our imagination, we have gradually expanded further. It is now 2025 and instead of frustration, we now have fresh tomatoes, pumpkins and a sense of community in our neighbourhood. Are there any pieces of land near you that need attention?

Neelakshi Joshi is a postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development in Dresden, Germany, who thinks about socioecological transformations by day and plants guerilla gardens by night.